This post is part of a series.

- Part 1: Let's Build A Feature Switch Rules Engine

- Part 2: This Post

Feature switch syntax

The feature switch syntax we decide on will be based on where the switches are being stored, whether or not rules are grouped together, and what type of external tooling we have.

Before deciding on what a feature switch looks like, you’ll need to ask yourself a few questions.

Database or filesystem?

Perhaps the biggest question to ask is where to store/retrieve your feature switches.

Here are some of the key considerations:

- A database is automatically distributed, making the switches accessible anywhere the database can be accessed. While storing in git would mean you need a way to distribute the files to any production server that needs them.

- Storing in git means that you can take advantage of code review processes to gate changes, but it might also slow down how quickly those changes are rolled out.

- Storing in git allows developers to test their feature switches in a local file without having to use a staging database.

- Git logs provide a built in audit log of changes, whereas this is something that you’d need to build yourself if they were stored in a DB.

| Database | git | |

|---|---|---|

| Propagation | Immediate, automatic | Needs to be setup |

| Audit trail | Needs to be built | Automatic |

| Code review | Needs to be built | Automatic (if already setup) |

| Local tests | Requires dev DB | Uses local files |

Generally speaking, going with a database will require more tooling to be built but provides faster propagation.

I would definitely lean toward file-based unless you absolutely need immediate propagation or are unable to distribute files to your services after they’ve already been deployed.

Should a feature switch be able to change multiple values?

It’s not unusual for developers to want to change two or more features with a single rule. You could imagine setting several values based on a rule like deviceOS == 'iOS', for example.

The logic required to support this isn’t too complex, so I would definitely lean toward allowing multiple values for a single rule.

What sort of metadata should I store with my feature switches?

This largely depends on your organization. At the least, you will want a name / description for your switches. Some organizations may also want to define an owner and/or oncall contact information.

Where do default values get stored?

In a relational database you may want to setup a default_values table. In a file-based system, you could have a separate file that stores all default values, but it might feel more natural to store defaults along with the rules that can change them.

Should there be any logical grouping of feature switch rules?

It’s very common to have multiple rules that all impact the same feature names, creating an implicit relationship between those rules. It will be helpful to codify these relationships into something more explicit. For a file-based system, I would recommend each file contain a group of related rules. In a relational database, you would create a groups table and a related rule_groups association table.

How do we handle conflicts?

In even the most basic feature switch ecosystem, you will run into the case where multiple rules match, but set conflicting values for the same feature name. We will need to define a priority to our rules, either implicitly (eg, prioritizing rules based on the order they were defined) or explicitly (eg, assigning each rule a number and prioritizing based on that number).

Choices

For this series, we will:

- Store our feature switches on a filesystem in YAML format

- Group rules together that modify the same features into a single file

- Allow a single rule to change multiple feature values

- Store name/description as our only metadata

- Store default values for features along with the switches that set them

- Use an implicit priority for dealing with conflicts. Rules defined further down in the file will take precedence over those defined earlier

Let’s take a moment to walk through a skeleton feature switch file.

1fs_group:

2 name: "Color scheme based on locale + device"

3 feature_switches:

4 - description: "White background for Canadian users"

5 featureValues:

6 - backgroundColor: "white"

7 - foregroundColor: "red"

8 rule:

9 <rule definition intentionally left for later>

10 - description: "Red background for older iOS users"

11 featureValues:

12 - backgroundColor: "red"

13 rule:

14 <rule definition intentionally left for later>

Each file defines a group of logically-connected feature switch rules. Above, we have 2 separate rules in a single file that both deal with changing the color scheme. The first rule targets Canadian users and sets both a backgroundColor and foregroundColor. The second rule targets iOS users running an older version of our app and only sets the backgroundColor. Note that the second rule is given a higher priority because it is defined later in the file.

There’s a little bit of nuance in dealing with conflicts here. For example, what do we do if the user is both Canadian and using an older iOS device? Technically, they only conflict on the backgroundColor. However, if we assign the foregroundColor from the first rule ("red"), and the backgroundColor from the second rule (also "red"!), we’ll run into a terrible user experience (and perhaps unexpected behavior from the developer’s point of view).

We also need to consider the scenario where a rule in a separate file might also impact the backgroundColor or foregroundColor. How do we resolve cross-file conflicts?

We can solve these problems by imposing some new restrictions:

- Every rule in the same group must provide values for the same set of features. Meaning if one rule in the group provides a

backgroundColorand another rule providesforegroundColor, then all rules in the group must provide both abackgroundColorandforegroundColor.- Two files cannot provide a value for the same feature. This means that there can only be one file that provides a value for

backgroundColorand we do not need to worry about rules that conflict in other files.

With these restrictions in place, we can further simplify things by specifying default values for each of those features at the top-level of our group. Now rules must either specify all values explicitly, or fallback on default values implicitly.

1fs_group:

2 name: "Color scheme based on locale + device"

3 defaults:

4 - backgroundColor: "black"

5 - foregroundColor: "white"

6 feature_switches:

7 - description: "White background for Canadian users"

8 featureValues:

9 - backgroundColor: "white"

10 - foregroundColor: "red"

11 rule:

12 <rule definition intentionally left for later>

13 - description: "Red background for older iOS users"

14 featureValues:

15 - backgroundColor: "red"

16 # there is an implicit foregroundColor: "white" from the

17 # defaults section above

18 rule:

19 <rule definition intentionally left for later>

Older iOS users will now have a backgroundColor of "red" and a foregroundColor of "white", thanks to our default values.

Rule definitions

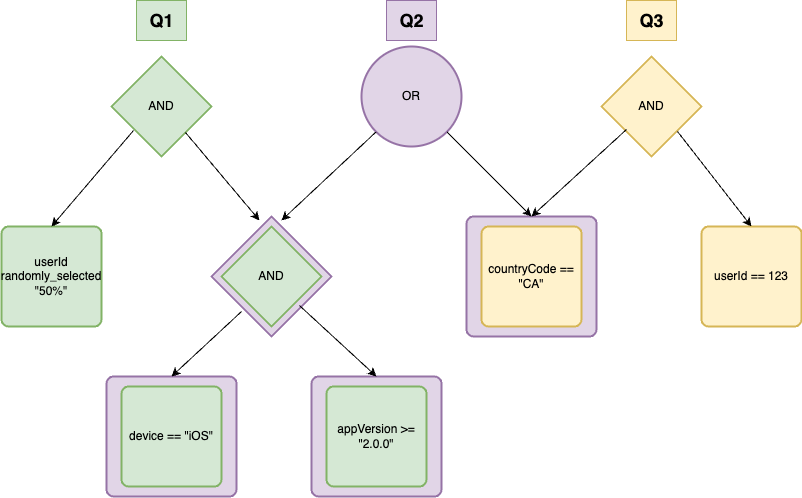

As mentioned in Part 1, our eventual goal is to take our rule definitions and convert them into a graph containing many queries, where each query can be represented as a tree.

If we modify things slightly, we can actually visualize each query as an expression tree, which will help us when it comes time to defining a storage format and parsing these queries.

We have several options for how we format our rules, each with pros and cons that depend on the ecosystem we’re building on top of.

Defining our rules in a tree-like format

One of the easiest formats we can parse is one that already looks like an expression tree.

1fs_group:

2 name: "Color scheme based on locale + device"

3 defaults:

4 - backgroundColor: "black"

5 - foregroundColor: "white"

6 feature_switches:

7 - description: "White background for CA users + newer iOS users"

8 featureValues:

9 - backgroundColor: "white"

10 - foregroundColor: "red"

11 rule:

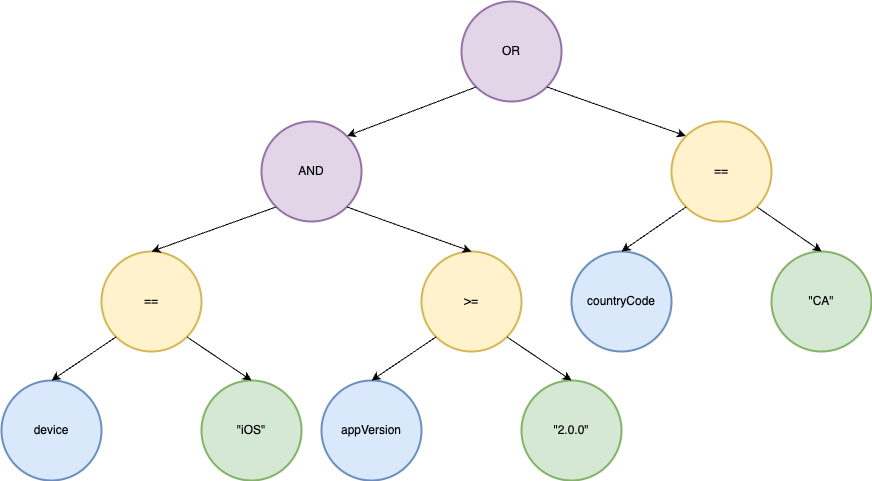

12 or:

13 - and:

14 - "==": ["device", "iOS" ]

15 - ">=": ["appVersion", "2.0.0"]

16 - "==": ["countryCode", "CA"]

This format assumes that each operator will contain a 2 item list (its operands). Building an expression tree from this format is fairly trivial. We would just need to traverse our rule, adding a new node for each operator and then adding each item in an operator’s list as its children.

While this format optimizes the parse codepath, it can be cumbersome for humans to read and write. This might be a good format if you have the right tooling to support it. You would likely want:

- A UI that takes the rules in a more human-friendly format and then does the conversion afterwards, and/or

- Robust tooling for developers to test and verify their rules before submitting them

Using prefix notation

Another easy-to-parse format is prefix notation, where operators appear before their operands. In mathematical terms, A + B * C becomes + A * B C. This again fits naturally into an expression tree, since each node in the tree is followed by it’s left and right children.

Let’s take a look at what that might look like using the same example.

1fs_group:

2 name: "Color scheme based on locale + device"

3 defaults:

4 - backgroundColor: "black"

5 - foregroundColor: "white"

6 feature_switches:

7 - description: "White background for CA users + newer iOS users"

8 featureValues:

9 - backgroundColor: "white"

10 - foregroundColor: "red"

11 rule: "OR AND == device 'iOS' >= appVersion '2.0.0' == countryCode 'CA'"

This format again optimizes the parse codepath. Since each operator is followed by its 2 children, parsing would mean: (1) tokenizing the rule expression, (2) adding the operator as a node in our expression tree, and then (3) adding the next two tokens as its children.

We can make the expression a little more readable by adding some parentheses and commas. Doing so makes it a little easier to see which operators belong to which operand:

OR(AND(==(device, 'iOS'), >=(appVersion, '2.0.0')), ==(countryCode, 'CA'))

In my opinion, this still is hard to reason about.

Back to infix notation

I specified our example rules in Part 1 using infix notation for a reason: it’s the same notation that most people are familiar with already.

1fs_group:

2 name: "Color scheme based on locale + device"

3 defaults:

4 - backgroundColor: "black"

5 - foregroundColor: "white"

6 feature_switches:

7 - description: "White background for CA users + newer iOS users"

8 featureValues:

9 - backgroundColor: "white"

10 - foregroundColor: "red"

11 rule: "countryCode == 'CA' OR (device == 'iOS' AND appVersion >= '2.0.0')"

Definitely easier for humans to reason about! We are going to choose to optimize for human readability and move forward with infix notation.

The problem is that it is not trivial to parse. Luckily there are plenty of libraries out there to help with this. In the next article, we’ll define a formal grammar for our rule expressions and build a parser that formats our rules into expression trees.